A LITTLE OF MY STORY

When I visited Odisha in February of 2024 for a family wedding, I joined my brother and sister-in-law to pay a visit to Lord Jagarnath towards the end of our stay. Visiting Odisha feels incomplete without a visit to Puri. At the same time, it is believed that if Lord Jagarnath does not wish it may not happen. So all three of us were excited that we could make time to take the long drive. On our way back my sister-in-law expressed her wish to buy artwork from Odisha.

For quite some time I had harbored a deep-seated desire to visit Raghurajpur, ever since learning that this village had been declared a ‘Heritage Crafts Village’ by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage in 2000. Raghurajpur’s antiquity and cultural significance, particularly as the birthplace of the Gotipua dance form crucial in the revival of Odissi classical dance, intrigued me. Renowned for its artistic heritage, it’s often said that everyone in this village is an artist. Nestled between Puri and Bhubaneswar, this quaint village held a special allure for me. With my brother and sister-in-law’s flight scheduled for later that night, I eagerly proposed the idea of a quick detour to Raghurajpur on our return.

Our driver, who was familiar with the area, suggested that it would only be a few miles detour. He mentioned that if we wished to avoid shopping in the city, we should be able to make it to Raghurajpur before the flight. Intrigued by the idea, all three of us agreed to take the detour. Despite not having any contacts or a specific address to guide us, I was confident that our curiosity would lead us to somewhere interesting.

As the clock ticked past noon, we finally reached a village. The sun beamed relentlessly, casting its harsh rays upon us. To my surprise, the scene before us was far remote from the picturesque image I had envisioned. Instead of quaint cottages and neatly paved paths, we were greeted by a dirt road flanked by modest homes, amidst ongoing road constructions. Eventually, our journey came to a halt as the car could no longer advance. Stepping out, we sought assistance from a passerby. With unwavering confidence, he motioned for us to follow him. Trusting his guidance, we proceeded without hesitation, eager to discover what lay ahead.

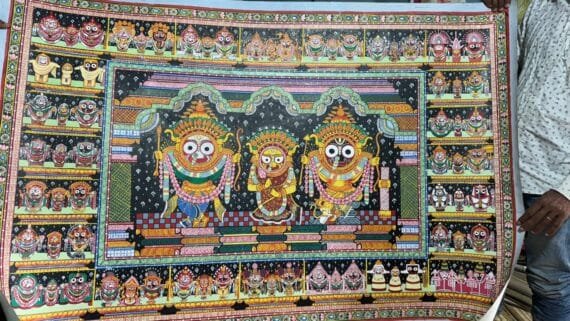

Before long, we realized that the passerby had led us to his own home. Despite our initial apprehension, we decided to follow him. A small old home. Passing through the ongoing constructions on the ground floor, we made our way upstairs. What awaited us was beyond our expectations – though the rooms were not glamorous the walls were adorned with a stunning array of intricate artworks. Some pieces were neatly framed, while others remained rolled up like tubes, waiting to be unveiled. We found ourselves captivated by the craftsmanship displayed in each piece. Eventually, my brother and sister-in-law selected a few pieces of varying sizes to purchase. It was a challenging task to choose amidst the abundance of exquisite artwork available, a testament to the talent and creativity of the village artisans.

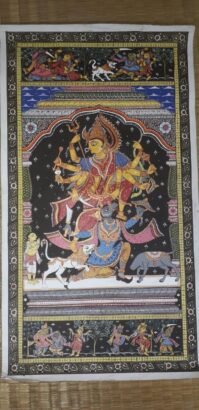

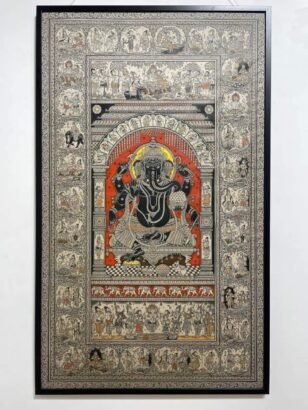

What inspired me to pen this blog is the captivating process behind these artworks. ‘Patta’ in Sanskrit means ‘cloth’, whereas ‘Chitra’ translates to ‘painting’. The process of crafting the base for painting, known as Patta, is complex. Old cotton saris, starch-free, are layered atop each other and stuck together using a paste made from tamarind seeds soaked in water for 2-3 days, ground, and cooked to make a paste called ‘Niryaskalpa’. Wood apple gum, or ‘Kaitha’, is mixed with the tamarind paste. Once the desired thickness is achieved with glued layers, the cloth is sun-dried, completing the Patta-making process. Soft clay stone mixed with tamarind paste is then applied to the Patta’s surface, which is smoothed by rubbing with a rounded stone or wooden block.

All-natural ingredients are used to prepare colors for Pattachitra. For instance, white is derived from grinding and heating sea-shells to create a milky paste, green from green leaves and stones, and black from thickened smoke collected under an earthen plate. Red comes from ‘Hingula’, a local stone in Odisha, and yellow from ‘Harital’. ‘Khandaneela’ yields blue. These primary colors bear immense significance, representing emotions in a story: white for laughter (Hasya), yellow for astonishment (Adbhuta), red for fury (Raudra), blue for Krishna, and green for Lord Rama. Mixing primary colors in specific ratios produces a palette of approximately 120 colors. Coconut shell bowls are used for blending, and brushes made from mouse hair provide a delicate touch, while buffalo hair and keya root are used for coarser brushes. (ref: https://hasthkala.in/)

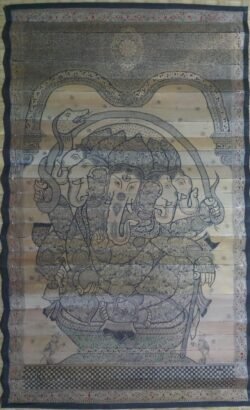

On the other hand, Pothi Chitra, an indigenous art form involves engraving motifs and figures onto palm leaves. The process begins by sun-drying the palm leaves for about three months, then soaking them in water and treating them with turmeric solution for longevity. Afterward, the treated leaves are tied together in segments and crafted into scrolls. Artisans employ an antique tool—an iron needle with a sharp point—to intricately engrave the drawings onto the palm leaves. Following this, pure lamp-black is applied and rubbed onto the leaves to fill the etched grooves. Excess black powder is then washed off with soap and water, revealing finely detailed artwork on the palm leaves.

Our serendipitous encounter brought us to the abode of a 78-year-old Guru, Sri Maga Nayak, an award-winning artist in Nayak Patna village though we intended to reach Raghurajpur. He is renowned for his unparalleled mastery over Pothi Chitra. In ancient times, this technique was used to document Sanskrit verses or jatakas (horoscopes) by engraving them on palm leaves to create Pothis. However, this tradition, dating back over 900 years, finds its modern resurgence through Guru Maga Nayak in Pothi Chitra where the artwork is engraved instead of Sanskrit verses.

Pothi Chitra has received its GI tag, originating from this village, with credit to Sri Nayak. Not only has he pioneered the concept, but throughout his life, he has also imparted his knowledge to the next generation, ensuring its preservation for posterity. I later learned that Dr. Jagannath Mohapatra one of his contemporaries from the nearby village, Raghurajpur, pioneered the Pattachitra. Both were disciples of Hadubandhu Mohapatra who was then a Sadhaka of Devi, Kanaka Durga.

All of Sri Maga Nayak’s children and their families are not only his disciples but also actively involved in painting. He has been running his Gurukul teaching at no cost to many students from nearby villages. As part of their women empowerment project, the Aditya Birla Institute also funds 40 women to come and learn this traditional art from Sri Nayak daily. These workshops run from 10 am to 5 pm every day. His daughter, Swapna Manjari Nayak, has even received a presidential award for her outstanding work in Pothi Chitra as well.

Recently, one of their most expensive and sizable art pieces among many was commissioned by the Ambanis for their prestigious Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Center in Mumbai. This is just one of several significant orders they have received, underscoring the widespread recognition and demand for their remarkable craftsmanship. Exclusive artworks from this very old rustic home have found their way to many different countries.

Sri Nayak’s sons, Prasanna and Prasant, meticulously guided us through the diverse range of artworks created using various techniques. Among the highlights were Saura tribal paintings, crafted on silk fabric, and pattachitras and pothi chitras. The paintings we observed predominantly depicted mythological characters or scenes from village life, each intricately detailed and rich in cultural significance. Through their masterful craftsmanship, Sri Nayak’s family brings these timeless traditions to life.

Another compelling reason that drove me to write this blog is the recurring theme found in all these art forms, centered around Srikrishna and his life. Gopis and Radha also hold significant relevance in this context. Recently, I had the privilege of publishing a book titled ‘Ashtanayika- tatwa o kabita’ (‘The Eight Heroines: Essence and Poetry’), delving into the intricacies of the romantic moods of women as elaborated in Natyashastra. Over centuries, these emotions have been infused into various art forms, including music, dance, and sculpture. During the medieval Bhakti movement, this concept transcended to miniature paintings, elaborating on timeless stories. I have always sensed an external guiding force aiding me in the writing and publication of this book, further deepening my connection to these profound narratives. The deep spiritual significance embedded within these artworks resonates with me on a profound level, inspiring me to share their beauty and significance with others through this blog.

Hence, I couldn’t shake off the feeling that there was a divine purpose behind my serendipitous visit to this village and its gurukul. Upon returning, a strong urge overcame me: I felt compelled to ensure that my book found its rightful place within this esteemed institution. Who knows, perhaps one day, inspired by the profound themes of the Ashtanayika, masterpiece artworks will emerge from these very walls, further enriching the legacy of this ancient art form. This journey has not only deepened my appreciation for the rich cultural heritage of our land but also reinforced my belief in the interconnectedness of art, spirituality, and divine guidance.

Maneesh Srivastava

03/19/2025Raghurajpur holds a special place in my heart. I visited with my late mother during my first trip to Odisha, and we fell in love with the marketplace and local art. It’s a must-visit detour when traveling between Bhubaneswar and Puri.

Manorama Choudhury

03/19/2025Thank you for sharing your experience visiting the village. I am glad this brought a sweet memory with your mother!

ପ୍ରକାଶ ପ୍ରଧାନ

03/19/2025Very nice. Keep doing promoting such valuable arts.

Manorama Choudhury

03/19/2025Thank you for your encouragement!